Most questions I had about religion and its practice stemmed from the paths which we have been handed down. I’ve been reading about these for a couple of weeks now, and the material that I came across made for a mighty interesting explanation. These were constructs based on circumstance and have shaped every aspect of our religion (and thereby spirituality). This post is mostly to do with Hinduism as I do not have the grounding to dig into how paths evolved in other religions. But I would assume those would have come up in a similar way too; and if readers follow a different religion, they would undoubtedly find similarities with their practice.

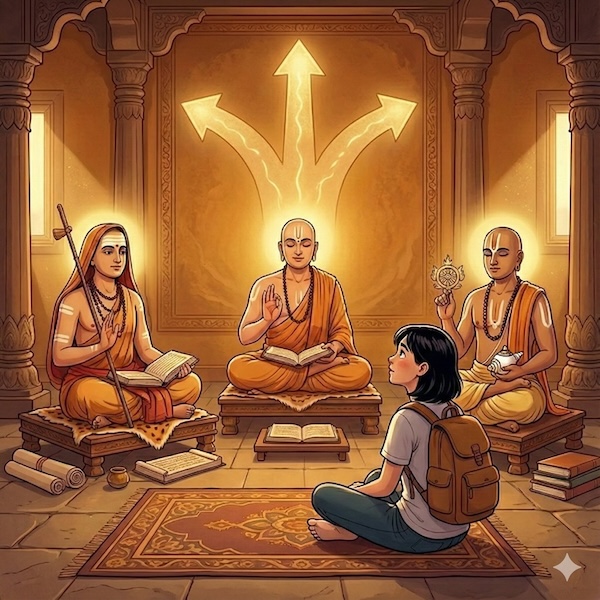

The timeline I find as most convincing is that the vedas were composed / expressed / compiled around 4000-5000 years ago. So lets say between 2500-1500 BCE. Our 3 main schools of thought – Advaita, Visishta Advaita, and Dvaita came about quite recently going by that timeline.

Adi Shankara, who propagated Advaita, was from the 8th century (~788-820 CE).

Visishta Advaita was propagated by Ramanujacharya who came in the 11th century (~1017-1137 CE).

Madhvacharya came up with Dvaita in the 13th century (~1238-1317 CE).

So religion based on vedic literature and practices was already around for over 2500 years before the first of the ‘reformers’ came about in Hinduism. There had to be a logical reason why they found it prudent to redefine an ancient set of practices.

Adi Shankara found that Hinduism was fracturing because of mindless practices which weren’t anchored in real understanding. He termed it Mimamsa. By that period (8th century CE), Buddhism had dominated much of the landscape intellectually by unlocking people’s curiosity, by allowing people to ask questions, and by providing logical answers. Shankara found the need for a unifying logical framework to restore the authority of the Vedas. So he decided to shift focus from ritual-centric practices onto the ultimate reality – Brahma Satyam, Jagam Mithya.

It worked beautifully, unifying all sects – Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism – by saying that all deities are forms of the One Brahman – Advaita. It was intellectually brilliant and brought about a religious rejuvenation.

Ramanujacharya, in the 11th century, found that Shankara’s theory of illusion (Maya / Mithya) made the world and personal love for God meaningless. He opined that if God is formless and if I am God, then who do I love? Since Bhakti was among the most popular choices for people to pursue, Ramanuja felt it had to be brought back into the mainstream; and for that, he argued that the world is real and not an illusion, and that if Vishnu (God) was the soul, we were his body. He explained it saying we are one with God organically, but still the two entities were distinct enough for us to love God – like saying I love my hand. This struck a chord with many as it made bhakti philosophical. We could now love God and also feel oneness with Him – Visishta Advaita.

Madhvacharya, in the 13th century, felt that non-dualism felt weak against the hard separation of man and God. This could be in part due to the new philosophies of invaders, who were sweeping the north of India. So he put forth a school of thought which established God as the supreme master and us as his people / servants / dependants. He made it total separation – Dvaita. Since the source was still the same texts, the goal was still liberation. But even in that quest for liberation, we could be a servant of God, who is our protector and master. This thinking provided emotional security to people, and brought about the concept of surrender – which is still the most popular path, one that most people starting out in religion find easy to accept.

To put the timeline into perspective, Shankara in the 8th century said God is Intelligence / Intellect to save Hinduism from Buddhist logic. Ramanuja in the 11th century said God is Love to save Hinduism from dry intellectualism. Madhva in the 13th century said God is Master to save Hinduism from internal arrogance (which he felt stemmed from the feeling that we are God) and from external threats. In this journey, they increased the distance between Man and God for practical purposes. Crux of this was that they felt Hinduism needed saving and rejuvenation, and they espoused a solution which they felt was most suitable for the times.

Unlike when the texts were originally written, this time around, the rubber met the road. These medieval philosophies didn’t stay in books. They shaped modern Indian life. The impact could be seen in how people pray, build temples, and even how they treat each other in daily life.

The dominant philosophy – even today – is Dvaita, since most people found it extremely easy to subscribe to. Much of our temple culture is built around this ‘transactional’ relationship. I can’t see the all-pervading God. So I will see God in the form of the idol and since I am the suffering devotee; I need to bridge that gap. Many practices like Archana, Abhishekam, Offerings, Vows etc came about. Much of religion became transactional – “I will break 108 coconuts if I get a US Visa”; astrologers saying that “performing this puja in that temple will relieve us of that Rahu-Ketu ill effect” and so on. The priest became the go-between for many of these practices between two parties – God and I. While reading about this, the next logical step was to see how worship and temples evolved and it is another fantastic subject to explore. That will be the topic of our next blog post.

The impact of Visishta Advaita can be seen through the Bhakti movement, which is among the most joyful of practices in our religion. Community worship and congregational chanting – as we see from large movements like Satya Sai, ISKCON etc – are its most common form. The idea is that since we are all parts of the same body, service to others is service to self which is in turn service to God. Service and Sankirtan are its expression. Instead of asking God for favours, the idea is to please God by loving everyone else – who are form of the same body, and through chanting His name. Many Guru-based communities emerged from this school of thought.

Advaita is mostly driven through intellectual practices like Jnana Yoga, Meditation, Mindfulness etc. The idea is that there is no external agency needed – like a temple or a congregation or even a priest. Self-enquiry needs just us with our mind. To aid us in this journey, Upanishads (which contain the summary of vedas), Yogic practices etc came about. Ashrams rose because of this, and the intellectually-driven often found these ashrams to be more beneficial in their journey than even temples.

The synthesis of these paths can be expressed thus – our society’s hardware (temples / rituals etc) are built on Dvaita, but the society’s software (Philosophies) are built on Advaita. That is where I found this mismatch to be most pronounced, since this leads us to talk high philosophy (Brahman and oneness and all) but practice low transaction (bribing the deity for favours). I’ve been bothered by this dichotomy for a long time now, but only now after this exercise over the last two weeks could I put it into words that made sense.

Wrapping this up, I think we need all three forms for the society to find itself spiritually. In effect, they are 3 ways of handling the same truth. Shankara knew it too. Else, why would he compose hymns and stotras to forms of God like Shiva, Krishna, and Annapoorna while espousing that we are God? He composed Bhaja Govindam to tell us that we shouldn’t get caught up too much in the philosophy and that it is not as complex as we make it to be. Dualism is easy for us to understand and follow. A child doesn’t meditate on the mother when its hungry; it just rushes to her for milk. But getting stuck there will make God a vending machine. As we grow, the youth connect better to congregations and to service to the society. Hence we see a lot of youngsters in that middle path. But getting stuck there will lead us to a ‘holier than thou’ attitude and give us moral superiority or even cause burnout. As we go forward in this journey, we come to a realisation that what we search for has always been within us, and that leads us to Advaita. This identity can only be found in silence. But the problem here is of premature intellectualism – thinking we have cracked the code when in reality we don’t even know ourselves.

The path reveals itself to people and pulls them towards it based on where we are mentally. In pain, we all cry to God and it is perfectly fine to be a dualist then, and not fake intellectualism. While in society, being a Vivishta Advaitin works best. We serve others and don’t pretend to be aloof. In silence, we be an Advaitin, inquiring into the self, till all three paths merge and joy is found in existence. This is Sadhana. This is all we keep doing till the truth is revealed. There is nothing else to learn! Think of it as a ‘Ladder of Maturity’.